This proliferation of global nuclear arsenals would inspire new generations of protestors and organisations such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), which had previously reached the zenith of its popularity in the 1960s. These movements would experience a revival under Thatcher’s government.

One of the most widely remembered anti-nuclear protests in the UK was the women’s peace camp at RAF Greenham Common. Recently marking the 20th anniversary of its closure in September 2020, the camp was created to counter the UK’s decision to use Greenham as the first site to house long-range, high-precision warheads known as ‘Cruise missiles’. The missiles were stored on behalf of the United States Air Force. The beginnings of the peace camp can be traced to a cottage in the Welsh village of Bettws. It was in this cottage that an organisation calling themselves ‘Women for Life on Earth’ began planning a protest march. The most efficient routes, suitable areas to stop in, and how supplies could be delivered along the way to aid the marchers were all important factors that were taken into consideration during a 9-month planning process.

The group, comprised of 36 women and 4 men aged between 25-80, assembled outside of Cardiff City Hall on the 27th of August 1981 before setting off for 10 days of walking. They would cover over 120 miles. Upon the group’s arrival at the RAF base in Berkshire, a letter was delivered to the base’s commander that stated the purpose of the march, in which protestors stated that ‘we fear for the future of all our children and for the future of the living world which is the basis of all life’. Whilst the march had been completed successfully, the protestors were disheartened that it had failed to capture public and media attention to the extent they had hoped it might. It was at this point that the idea to remain outside the base in permanent protest was conceived and put into action.

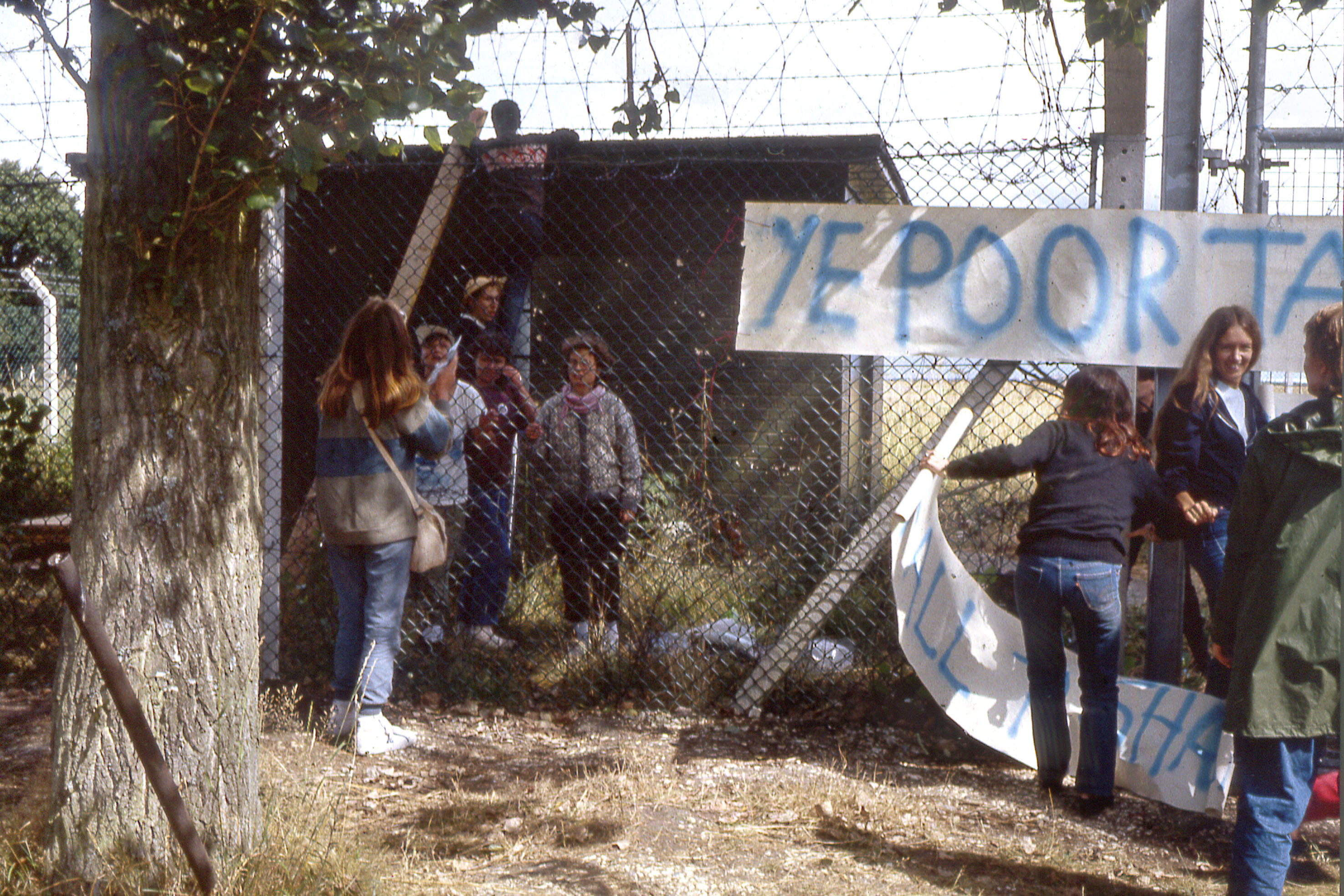

Whilst occupying the camp, protestors utilised non-violent direct-action methods, championed by Bertrand Russell and other first wave CND activists. This included sit-ins, linking arms around the base and chaining themselves to the camp’s entrance gates, a few times even managing to breach the base’s perimeter fencing to dance on weapon silo’s. These recurrent acts of civil disobedience aimed to gain publicity and garner support from the public. They were assisted during the site’s occupation by frequent visits from domestic and international journalists and news crews eager to report on new developments within the camp.

To build and maintain morale amongst the camp they sang traditional folk protest songs, as well as creating their own such as ‘Carry Greenham Home’. Photos of their children and loved ones were attached to the fencing that separated them from military personnel, serving as a reminder of who they were fighting to protect against the prospect of nuclear war.

It was decided in February 1982 that the camp would be occupied solely by women, a decision that led to the camp evolving into a nucleus for the feminist movement in Britain. As news of the camp spread and interest began to grow, fleets of coaches started arriving at the site to aid the women in their protest. Women from across the UK and throughout the world travelled to join the protest. Amongst their ranks, four women from the Faroe Islands journeyed to Greenham Common in solidarity.

“We heard about the camp in the media. I was living in Copenhagen at the time and was politically active, especially within the Faroese women's movement (in Copenhagen) and the peace movement. So, a few of us, from that environment decided to go to Greenham Common together. Women at the camp were quite surprised that a group of Faroese women were interested in the cause, not everyone even knew what the Faroe Islands were."

Jóna Olsen

Despite the camp inhabitants’ non-violent approach to protest throughout the 19 years the camp was occupied, regular and aggressive mass evictions and arrests were carried out, which led to tensions between protestors, the police and armed forces intensifying as time progressed. In an attempt to replicate the success of the Greenham women, Molesworth People’s Peace Camp was set up in the December of 1981 at RAF Molesworth in protest of NATO plans to deploy Pershing II missiles. The camp existed until 1990. Today, the Faslane Peace Camp is the only peace camp remaining and has been consistently occupied since June 1982, although the location of the camp has varied over the years. It was set up nearby the HMNB Naval Base Clyde in Helensburgh, Scotland in efforts to protest Britain’s current nuclear deterrent, Trident.

The legacy of the Women’s Peace Camp on both the feminist movement in the UK and the anti-nuclear protests is unmistakable. Many of these women were far from veteran demonstrators but rather, regular mothers, sisters and daughters worried for the fate they believed the world could be damned to. Their efforts inspired a new age of activism and over the years support for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament has continued to grow, with an anti-Trident march in February of 2016 being dubbed the ‘biggest anti-nuclear demonstration of a generation’. Whilst today the threat of nuclear war feels further from the horizon than in the era the Peace Camp was started, with nations continuing to upgrade their nuclear defence systems a call to join the fight towards a world without nuclear weapons will always be essential.